This recommendation is the first in a chain of events that could have major impact on over 200 ACICS-accredited schools that enroll more than 800,000 students. This Alert is intended to describe the process that might unfold and offer guidance to institutions that might be affected. The accreditation professionals on the Cooley Education Team stand ready to assist our clients in managing the effects of what may be an exceptionally disruptive period in American postsecondary education.

Since the passage of the Higher Education Act of 1965 (HEA) five decades ago, which created the federal student loan, grant, and work programs (collectively referred to as the Title IV Programs), institutional accreditation by an organization recognized by the Secretary of Education has been a core eligibility requirement for participation in the Title IV Programs. Although the number of accrediting agencies recognized by the Department has grown significantly over the years, and despite the fact that the maximum length of each grant is of a relatively short duration, denial of continued recognition has been an exceedingly rare occurrence.

Recent events, capped by the catastrophic failure of a very large postsecondary education company that resulted in the displacement of thousands of students, have called into question not only the oversight of accreditors recognized by the Secretary, but the very validity of the accreditation process itself. In this fraught environment, one of the largest accreditors, ACICS, faces the prospect of losing its federal recognition. This Cooley Accreditation alert discusses the background of this eventuality and its potential consequences, particularly on institutions accredited by ACICS and on their students.

The recognition process

The HEA requires each accrediting agency to meet very prescriptive statutory and regulatory requirements in order to be considered “a reliable authority as to the quality of education or training offered” and in so doing be recognized by the Department for the purpose of enabling institutions to participate in federal student aid programs. Prior to the expiration of a grant of recognition, which can last no longer than five years, an accrediting agency must submit a detailed application to the Department that documents the agency’s compliance with each of the recognition criteria set forth in the regulations. As part of the application review process, the Department publishes a notice of the pending review in the Federal Register and invites public comment on each accrediting agency that is up for re-recognition. Department staff is required to incorporate any public comments – and complaints – received into their analysis of the accrediting agency, along with any findings from on-site evaluations of agency processes such as training sessions, meetings, and in some cases participation in visits to institutions under review by the agency. The results of this review are summarized in a draft report, to which the agency is given an opportunity to respond before the staff report is finalized.

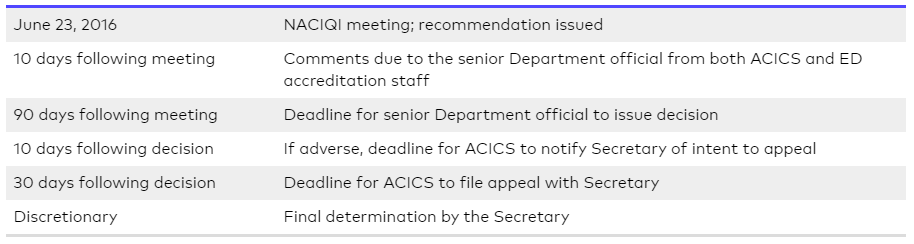

The final staff report is submitted to NACIQI for review and consideration at a public meeting. Representatives of the accrediting agency may make a presentation at the meeting, as may members of the public, including interested public officials. As its name implies, NACIQI is an advisory committee, and its action does not bind the Secretary, who is solely vested with authority to recognize an accrediting agency. The Committee can recommend approval of the accreditor’s recognition application, denial or termination of continued recognition, limitation or suspension of recognition, or deferral of action combined with compliance reporting pending a final decision. Once NACIQI makes its recommendation, both Department staff and the accrediting agency may provide written comments to the Secretary. The comments are due 10 days following the meeting at which the recommendation is made.

Although the Secretary of Education is by law responsible for determining whether to limit, suspend, or terminate the recognition of an accrediting agency, the HEA and applicable regulations mandate that such adverse action may be taken only after notice and an opportunity for a hearing. Pursuant to Department regulations, the initial deciding official is not the Secretary, but rather a “senior Department official,” referred to as the “SDO,” who reports directly to the Secretary regarding accrediting agency recognition. Within 90 days of the NACIQI meeting, the SDO must make a determination and notify the agency of her decision to approve, deny, limit, suspend, terminate, or require compliance reporting. However, if the SDO identifies other recognition standards with which the agency appears noncompliant that were not raised earlier in the review process, or if additional information pertaining to an agency’s compliance that was not previously in the record is brought to light, she may delay her determination in order to request additional information from the agency or refer the matter back to ED staff or NACIQI for further review.

Unless the agency appeals, the decision of the SDO is the final decision of the Department. The accrediting agency has 10 days to appeal the decision to the Secretary of Education, and 30 days from the date of the decision to submit a written appeal. An appeal to the Secretary stays the effect of the decision until it is finally decided by the Secretary, which means that the agency remains recognized. There is no time frame under which the Secretary must render a decision. The Secretary can take any action he deems appropriate, including a decision to approve, deny, limit, suspend, terminate, or require compliance reporting before making a final determination. Like the SDO, he may also choose to request additional information from the agency or refer the matter back to ED staff, NACIQI, or the SDO for further review. The accrediting agency may contest the Secretary’s decision in federal District Court, but, unless the action is stayed by the court, the decision becomes immediately effective and, in the case of denial or termination, the agency’s recognition is immediately removed.

The ACICS review

On June 15, 2016, the Department released a staff report recommending that the application submitted by ACICS for renewal of recognition, set to expire this summer, be denied. According to Department regulations, the likely timeline moving forward is as follows:

Importantly, ACICS’ recognition status continues until a final decision or ACICS voluntarily withdraws. Note also that although Department staff has recommended that the recognition of ACICS not be renewed, NACIQI – and the Department officials who will review and ultimately act on any NACIQI recommendation, up to and including the Secretary – have available alternatives other than non-renewal. For example, they could impose limitations on ACICS’s ability to accredit new institutions or programs, require a rigorous reporting regime, or, as the Department seems disposed to consider, require ACICS to operate under the supervision of an ED-appointed monitor.

Impact of denial of recognition on accredited institutions

If the Secretary withdraws the recognition of an accrediting agency, the HEA grants the Secretary discretion to grant institutions accredited by that agency provisional certification to participate in the Title IV Programs for no longer from 18 months from the date of the final decision to withdraw recognition. There are two important points related to this provision: First, the eighteen-month period is discretionary, and, second, fully certified institutions likely would revert to provisional certification.

It is important to note that a Provisional Program Participation Agreement (PPPA) gives the Department much greater control over an institution, substantially reducing the procedural rights an institution ordinarily enjoys. For example, an institution that is provisionally certified can have its PPPA revoked by the Department without advance notice and without the same due process protections that attend full certification. The Department may also impose a variety of conditions, such as requiring the institution seek advance approval for certain changes (e.g., the addition of new programs and locations). Furthermore, given the dearth of precedent, it is unclear how the Department would process institutional changes during that eighteen month period that ordinarily require accreditor approval, such as changes of ownership.

Regarding timing, the point at which the eighteen-month clock starts ticking depends on whether the agency decides to appeal the initial decision of the senior Department official to the Secretary. Although neither the HEA nor the implementing regulations expressly grant the Secretary discretion to continue the certification of institutions in any status in the event that their agency voluntarily withdraws its recognition, there is some precedent for the Department to allow schools to continue participating in the Title IV programs in such circumstances. In another instance, which occurred prior to the incorporation of the 18-month transition provision into the HEA, the then-Secretary continued the agency’s recognition for nine months coincident with his decision to allow the accredited schools to seek accreditation elsewhere; the Secretary’s action in effect deferred the effective date of the termination of the accrediting agency’s recognition, rather than affording an extension to institutions whose accreditation had lapsed by virtue of a loss of a recognized accreditor. Unlike ACICS, each the accrediting agencies in these cases accredited a very small number of institutions.

It is important to note that an accreditor’s loss of recognition can impact an institution not just with respect to participation in Title IV Programs, but also in the following contexts:

- State licensure agencies. Many states require schools to be accredited by a federally recognized agency in order to operate and/or grant degrees or certificates. In those states with licensure-by-means-of-accreditation, such an exemption would generally no longer be valid.

- Programmatic accrediting agencies. Many programmatic accreditors, even if not federally recognized themselves, only accredit programs at institutions that are institutionally accredited by a federally recognized accreditor.

- Department of Defense educational benefits. Institutions with a Memorandum of Understanding with the Department of Defense to enable military personnel to participate in tuition assistance programs must be accredited by a federally recognized accrediting agency.

- Veterans’ educational benefits. Programs that are not accredited by a federally recognized accreditor are subject to a more stringent review process and cannot be offered via distance education or a hybrid methodology.

- Student and Exchange Visitor Program. Failure to maintain accreditation by a federally recognized agency could be grounds for withdrawal of an institution’s ability to issue documents that enable a foreign student to enter the US and enroll as a student visitor, but SEVP has some limited discretion. By statute, however, SEVP-certified English as a Second Language programs that are not accredited by a federally recognized accreditor lose certification and the ability to issue supporting documentation for foreign student visas.

- Covenants in agreements with financial institutions. Some institutional agreements with financial institutions for loans or lines of credit include clauses requiring continued accreditation by a federally recognized accreditor.

- Private grant and scholarship funding. Many private grant and scholarship programs require an institution to maintain federally recognized accreditation as a condition for continued receipt of funds.

- Transfer credit and acceptance into programs at a higher-credential level. The academic policies of institutions into which students transfer or enroll for further credentials usually require that the credits or degree must be earned at a school accredited by a federally recognized accreditor in order to qualify for transfer or admission.

Thus, simply extending the period during which an institution can continue to participate in the Title IV Programs would not necessarily be sufficient to ward off significant adverse consequences from ACICS’s loss of recognition from the Department.

Parenthetically, while a number of states, specialized accreditors, and others include in their approval standards acknowledgement of accreditors that are recognized by the Council for Higher Education Accreditation (CHEA), it is highly unlikely that CHEA would continue ACICS recognition in the face of adverse action by the Secretary.

Seeking alternative accreditation

The HEA and its implementing regulations incorporate provisions designed to focus monitoring efforts on institutions seeking to be accredited by more than one federally recognized agency at a time. These rules are intended to avoid “accreditation shopping” and to impede the ability of institutions that are under the risk of adverse action from jumping to another accreditor. Thus, holding more than one accreditation at a time is acceptable only if the institution submits to each agency and to the Department the reasons, demonstrates to the satisfaction of the Department that there is reasonable cause, and selects one agency for purposes of establishing eligibility. Federally recognized accrediting agencies are prohibited from granting accreditation to an institution if the institution is under probation or an equivalent status imposed by another recognized agency, and also if the institution does not provide a “thorough and reasonable explanation, consistent with its standards, why the action of the other body does not preclude the agency’s grant of accreditation.”

There are also some alternatives to seeking a new accrediting agency such as merging into or being acquired by an institution that holds accreditation from a different federally recognized agency, but the feasibility of such options will likely vary by each institution.

We know that ACICS and the institutions it accredits are hopeful that the upcoming process does not result in the loss of recognition. The agency has been active adopting new standards and measures to remedy any perceived deficiencies. However, if the Department decides not to extend the current recognition and ACICS is unable to prevail on appeal, institutions will need to move quickly to pursue alternatives.

We plan to issue another alert following the NACIQI meeting, but in the interim, please feel free to contact us with any questions.

Notes

- The primary statutory provision governing accrediting agency recognition is Section 496 of the HEA, codified at 20 USC § 1099b, and the implementing regulations can be found at 34 CFR Part 602.

- Secretary King has designated his Chief of Staff (and former Assistant Secretary for Policy, Planning and Evaluation), Emma Vadehra, as the SDO.

- Absent an order of the Court, recognition does not continue during an agency’s legal challenge to contest the Secretary’s decision to deny or terminate. See 34 CFR § 602.38.